We need women–and especially women of color–in our tech classrooms modeling a female way of being a tech maker to our little girls.

We all already know this; it’s an obvious conclusion to come to if you think at all about the way women are underrepresented in technology today. But for some reason I woke up this morning feeling clearer than ever about why this is so.

I am not a “techie” and a year ago technology education was not something that I ever thought I’d care about. But I am fascinated with the way that representations affect our lives and our individual and collective possibilities on multiple levels.

What do I mean? Here’s an example: Although women were the leaders in the early development of the computer (math was seen as women’s work back then–just an extension of secretarial duties), women’s interest in technology steeply dropped off right at the moment that advertisers decided to start marketing computers as “toys” for “boys.”

In other words, how the field of computing was represented–and “gendered” in the process–has shaped the on-the-ground realities of who is actually involved with technology today.

How can this be? Are our very passions–our decisions about what we love to do and what we don’t want to spend our time on–dictated by simple stereotypes? Don’t we have choice? Can’t we decide to persevere against the grain if we really love something?

Some of us can, and some of us can’t. Adolescents may be especially ill equipped to go against the grain. Unfortunately that’s the exact moment when we start asking kids to make decisions about coursework that can affect the rest of their lives.

Thinking back on my own “tween” years, I can now see an alternate path toward technology that I might have gone down. My family moved in the summer between 7th and 8th grade, meaning that I spent a lot of time reading novels, writing in my diary, and going online to socialize with my old friends through instant messaging and proto social media sites.

In the process of spending so much time online, I taught myself basic html with the help of an old textbook my dad gave me and other online research. What began as just a way to feel connected to my friends became experiential learning; I wanted to make a website, so I figured out how.

But at some point, even highly self-directed students need guidance. There were no coding classes at my middle school, but there was a “new media design” course that taught things like photoshop and flash animation. I enrolled and was one of two girls in a class of 20-30 students, run by a male teacher. I remember that class mostly in flashes of feeling intimidated, self-conscious, and uncomfortable. When high school came around, I didn’t pursue my interest in technology.

I share this because I think it tells us something about where we fail adolescent girls with an interest in technology. The other girl in my new media design class was tomboyish and fit in (to an extent) with the rest of the class. I knew however that I couldn’t be like her; that model of girlhood just wouldn’t work for me. I was too quiet and too non-competitive. There was no role model to give me an idea of how I could enact the kind of femininity that felt right for me and be a tech maker at the same time.

Looking back, miserable 8th grade me was interested in really only 3 things: reading, writing, and coding. Two of those things are integral parts of who I am today and the work that I do. The third ended up dropping by the wayside.

On the flip side, I’m thankful for the things that I went on to learn about and experience after I turned away from technology. If I’d been able to immerse myself totally in computers and if I’d taken that on as my primary identity, I might not have developed my interests in poetry, colonialism, indigenous politics and a bunch of other things.

I wonder about this when I hear (sexist) arguments about how men and boys today are so victimized by feminism that they retreat into fantasy worlds, including video games and pornography. The idea is sometimes extended to technology, where people assume that guys who achieve prowess in technology are compensating for inadequacy in other traditionally “manly” endeavors like sports or–I don’t know–auto mechanics?

But the reality is, that idea is crap. People do coding and computer science because they’re passionate about it, not because they’re trying to hide other deficiencies. Stereotypes about boy-genius tech nerds, when they are positive (he’s a computer wizard!) or negative (he only talks to girls online) are offensive because they denigrate people’s passions, hard work, and achievements.

They’re also damaging because they limit everyone’s possibilities: Girls are excluded from tech because they’re unable to form identities as women and tech makers, and boys are sometimes pigeonholed into “boy” subjects. We need technologists with diverse interests and expertise who can connect contemporary technology with seemingly disparate fields of knowledge. This means we need women and the knowledge they bring from outside the tech world, and we need to encourage the tech-oriented boys we teach to make connections between what they know so well, and what they see around them when they’re not plugged in.

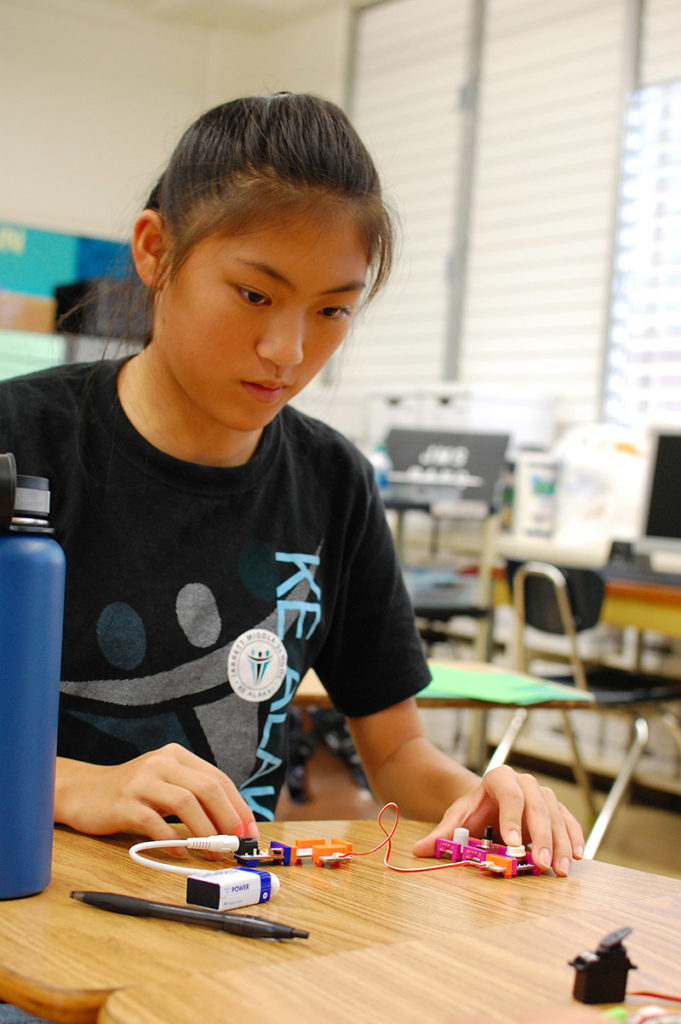

So, I’ll say it again: We need more women in our tech classrooms. Purple Maiʻa needs one for our after school class at Jarrett middle school. Email me: kmt.amos@gmail.com.